Our 10-year-old daughter has ADHD and what was the most unexpected part of supporting her was how my wife and I argued while trying to help. Is “help” the right word?

We wanted to help, we believed in our daughter, and we wanted to see her succeed, but the way we argued about how best to help Norah wasn’t helping at all.

All of it came to a head this year. We we’re two weeks into her fifth grade year, and each night had been a battle not only with our daughter, but also with each other.

Norah kept falling further behind despite her 504 plan, and everyone was frustrated.

I work in higher education, and most of my job is assisting college student athletes to succeed, many of them with documented learning disabilities. I like to think of myself as somewhat of an expert in this area, but at the same time, I also consider myself to be an expert at a lot of things, all of which are debatable if you ask my wife.

Mel also works in education. She works at our daughter’s school actually, so she has the inside track on her classroom expectations. She’s also read a dozen or so books on how to support a child with ADHD, along with searching the Internet endlessly for tips and tricks.

You’d think we’d be a dynamite team, and from a distance, it does look that way. We really should have been crushing this whole ADHD thing, and our daughter ought to have already been accepted to Harvard.

But we weren’t. Not even close to being on the same page with our daughter’s plan.

The problem was, we’re also both pretty strong headed, so instead of putting our heads together in a productive way, we just contradicted each other, both of us trying to take the wheel when assisting our daughter because “I know best,” and we ultimately ended up at each other’s throats.

We argued over where she should work, how long to set her timer, what is the best way to motivate her, how much she can accomplish in a given amount of time, and so on.

We argued, as our daughter sat there, looking up at us, trying to figure out what to do, and who to trust, when the reality is, she should have been able to trust both of us, because we both love the hell out of her.

A few weeks ago, on a Saturday afternoon, Mel and I were arguing over how to best help Norah with her math homework, when she slammed her math book shut, and ran upstairs, crying.

Suddenly all three of us were in Norah’s room, Norah hiding behind the dresses hanging in her closet, her knees in her chest, Mel and I trying to talk her down.

Mel said, “We’re all on the same team.” And Norah said, “It sure doesn’t feel like it.”

“What do you mean?” I said.

“No one listens to what I want. I’m the one learning,” she said.

Mel and I made eye contact and realized that although we thought we knew what was best for our daughter’s education, we failed to fully involve her, causing Norah to feel like her voice didn’t matter and preventing her from buying into her own education.

It’s funny, really… everyone in the room had the same goal, and yet everyone had a different idea on how to reach it, and no one felt like they were being listened to. Mel and I had our own agenda, and our own feelings of how to best help our daughter, but never once did we look across the table and ask Norah what she needed.

I think as parents, we fall into this trap.

We assume that we know what’s best for our kids, when the reality is, they might actually have a pretty good idea of what’s best for themselves.

This can become really apparent when assisting a child with ADHD. They usually have to work twice as hard as the students around them, causing them to feel anxious about their own abilities, and often times they feel as though school, learning, education, all of it is just too hard.

Getting them to buy in is so incredibly important, because without buy in, they can easily just quit.

Quitting was the last thing Mel and I wanted.

One thing I have to say about my daughter is this, she doesn’t miss a beat when she’s ready to state her opinion, and I do feel lucky that she felt comfortable with Mel and I to tell us what she wanted, rather than simply shutting down.

As Mel and I sat in Norah’s closet, listening for the first time, Norah told us what she needed.

She mentioned how we kept discussing her education when she wasn’t around, usually in whispers, when what she really needed was to be involved. “I don’t like you two talking about me when I’m not there.”

I think this, right here, was what bothered her the most. She felt in the dark, and you know what, she was right. She needed to be part of the conversation.

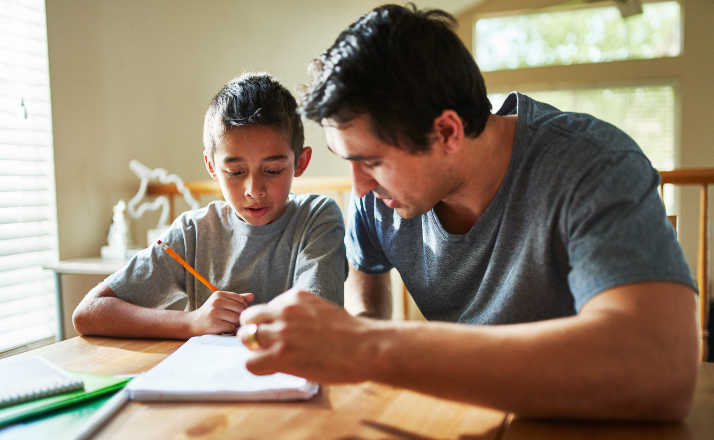

Later that day, all three of us sat down at the table and came up with a plan using everyone’s input. We discussed what Norah felt was working, and what wasn’t.

We discussed distraction free environments, and motivation, and study schedules, and by the time it was all said and done, we started to look like a team. But most importantly, Norah felt like she had a say in her own education.