Remember back in March 2020, during the first wave of Covid when we shut the schools down, and we all told ourselves it was supposed to last for just a couple of weeks?

And remember how there was a feeling of solidarity that we could beat this invisible threat, but then it just kept getting worse. And worse.

And then we went to remote schooling?

One of the biggest unknowns at the time was how much damage pulling kids out of school could cause them.

At my house, we ended up homeschooling because we couldn’t access the internet to even do remote learning.

My family felt left behind during a very confusing and scary time, and I saw my kids’ behavior deteriorate with every passing day.

Online, parents everywhere posted about how anxious and depressed they were, how angry their kids were, how hopeless everything felt. The news sure as hell didn’t help.

But now, science is wondering the same thing we’ve been arguing about for nearly two years; does closing down a school affect a child’s mental health, behavior, and well-being?

JAMA Pediatrics published a review of 36 studies from 11 countries that focused on kids from age zero (pandemic babies!) to 19-years-old to see how everyone fared when the world went into lockdown. And the results?

Well, they read part no-shit-Sherlock and part hopefully-we-don’t-fuck-this-up-next-time.

The total amount of information in these 36 studies came from 79,781 kids and 18,028 parents and what they experienced from February to July 2020, which was the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic.

In the published findings, the review team noted that

“the potential epidemiologic benefits of school closures during broader social lockdown measures for controlling infectious diseases should be balanced with the potential for adverse mental health symptoms and health behaviors among children and adolescents.”

What the researchers saw in this review, was just how much loss kids and families experienced during the first and subsequent lockdowns from the pandemic.

And when you look at the staggering list of what was taken away, it becomes clear pretty quickly why and how kids everywhere seem to be falling apart at the seams.

Because it wasn’t just relationships with other kids and teachers, it was a total social breakdown that might have longer-lasting damaging effects on an entire generation that we can’t even wrap our heads around yet.

Here is a list of things that kids lost, according to this review of 36 studies.

- Access to food.

- Access to services such as counselors.

- Access to services for learning disabilities.

- Access to warmth and safety.

- Surveillance for child abuse or neglect.

- Social interactions.

- Relationship building.

- Reliably predictable schedules.

- Health services.

- Menstrual hygiene supplies.

- Physical activity.

25 of the 36 studies (or 60%) focused on mental health and well-being specifically and reported that 53.3% of girls and 44.0% of boys reported anxiety and depression.

The report notes that rates of suicide did not appear to climb; however, in one example of suicide rates, Covid lockdown measures were considered a contributing factor in 48% of the 26 suicides in England.

Kids in lockdown didn’t get enough sleep.

In some of the material reviewed by JAMA, insomnia rose by 23.2%. That doesn’t bode well for kids who need rest for their growing bodies and to help keep their mental and emotional health regulated.

Any parents can tell you that a kid who doesn’t get enough sleep is grumpy as hell.

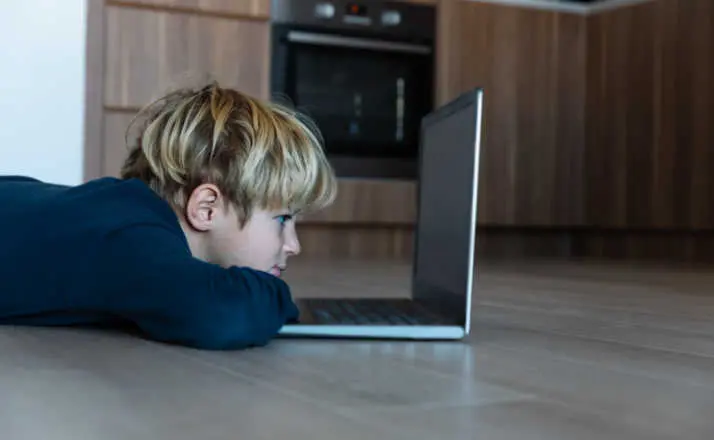

Screen time increased across the board.

Depending on what part of the world your kid lives in, screen time rose by as much as 70% or a five-hour increase a day.

They also found that kids ate far more junk food and experienced a significant drop in the overall amount of fruits and vegetables they consumed during the lockdown.

So, what does all of this information mean for our kids’ mental health?

If we can see data from this review of studies that show how much kids stand to lose when we take them out of school, and we square that with data that says that Covid isn’t spreading in the schools the way we all feared it would, does that mean we’ll adjust how we approach balancing public health against a virus with the mental and emotional well-being of our kids?

At best, we can use this information as parents to figure out best practices for our own families.

We know that a healthy diet, good communication, and a decent amount of sleep can go a long way to keeping our kids healthy.

At worst, we won’t learn our lessons, and our kids will grow up with problems we can’t even fathom yet.